A week ago, two important feasts were celebrated throughout the Cabrini world: the anniversary of Mother Cabrini’s Beatification (13 November) and the Foundation of the Institute (14 November).

We share two initiatives that wanted to remember in a special way these two important passages in the history of the Congregation of the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart of Jesus:

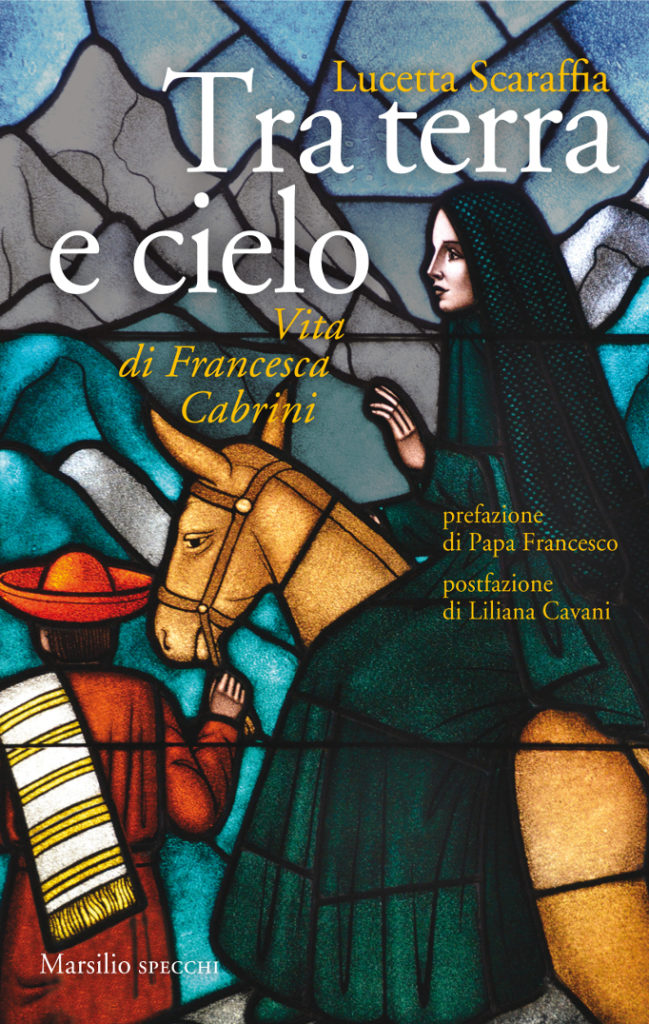

the first concerns the article for “Terra e missione” by Sister Assunta Scopelliti entitled – Francesca Cabrini and her journey “Between earth and sky” – written about Lucetta Scaraffia’s 2017 book that traces her adventurous story a century after her death: the story of the Lombard woman born on 15 July 1850 and who died in Chicago over a century ago, on 22 December 1917.

The second one concerns the exhibition ‘Mother Cabrini, the angel of migrants’ inaugurated on 13 November at the Cabrini Museum in Codogno, a place that saw the birth of the first Institute founded by Mother Cabrini.

Francesca Cabrini and her journey “Between earth and sky”

A week ago, two important feasts were celebrated throughout the Cabrini world: the anniversary of Mother Cabrini’s Beatification (13 November) and the Foundation of the Institute (14 November).

We share two initiatives that wanted to remember in a special way these two important passages in the history of the Congregation of the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart of Jesus:

the first concerns the article for “Terra e missione” by Sister Assunta Scopelliti entitled – Francesca Cabrini and her journey “Between earth and sky” – written about Lucetta Scaraffia’s 2017 book that traces her adventurous story a century after her death: the story of the Lombard woman born on 15 July 1850 and who died in Chicago over a century ago, on 22 December 1917.

The second one concerns the exhibition ‘Mother Cabrini, the angel of migrants’ inaugurated on 13 November at the Cabrini Museum in Codogno, a place that saw the birth of the first Institute founded by Mother Cabrini.

“Between earth and sky”, a book by Lucetta Scaraffia, tells the story of the Lombard woman born on 15th July 1850 and who died in Chicago over a century ago, on 22nd December 1917. She was beatified on 13th November 1938 by Pius XI and sanctified by Pius XII in 1946, before being proclaimed “Patroness of all emigrants” by the same pontiff in 1950.

The text recounts the network of her relationships, not always easy to manage, but Francesca like a mother is not afraid to ask for concrete commitment and compassion for her children. When Leo XIII asked her to give up her missionary dream in China to take care of the Italian emigrants in America, Francesca obeyed and a world opened up before her: that of the hundreds of thousands of human beings who sought work and bread far from their homeland, risking long and often dangerous journeys in unknown and hostile lands. She had understood that this was not a temporary phenomenon but the emergence of a new historical era in which the ease of modern means of transport allowed the movement of huge masses of people, thus reshaping entire parts of the globe.

Francesca had foreseen that modernity would be marked by these huge migrations and by uprooted human beings, in crisis of identity, often desperate and lacking the resources to cope with the society in which they had to integrate. Her response to the new course of history was to build large, beautiful and lasting works of welcome and assistance: her sisters continued their work even when the origin of the migrants changed, even when other faces, other colours and other peoples followed in their institutions.

Francesca Cabrini understood that it was not enough to help them materially, but rather to teach them the language of the country of arrival, to cure them if they were ill: their self-respect, their profound identity was linked to their religious roots, to their bond with God. And she and her sisters set out to reconnect this bond in the men who went down into the mines, in the prisoners, in the abandoned boys who lived in the illegality of the urban suburbs. Integration in the new country meant acceptance of rules and laws, and dignity: these were the goals he wanted all migrants to achieve. These were the goals he wanted all migrants to achieve, goals that are still valid today, and which involve recognising and respecting their own and others’ religious roots. A concrete and at the same time far-reaching project that extends to the whole world. “The world is too small”, she said – but it also opens up to future times. All this helps us to understand why a woman became the patron saint of migrants, a woman who was able to realise her own feminine qualities – warmth, welcome, concreteness in grasping the needs of others, gratuitous solicitude towards the weak – alongside an overall vision of the changes that were upsetting the world.

Francesca Cabrini: charity and prophetic spirit

Francesca Cabrini knew how to unite a great charity with a prophetic spirit that made her understand modernity in its less positive aspects, those aspects that involved the wretched of the earth and that intellectuals and politicians did not want to see.

For this very reason, Francesca Cabrini is very relevant today and still teaches us the way to face the epochal phenomenon of migrations by combining charity and justice. Francesca Cabrini grew up in a large family. She became a nun: she dreamed of becoming a missionary in China from a very young age. She realised her dream of going to the other side of the world, not to China but to America.

In the course of his life, he will make twenty-eight crossings of the Atlantic Ocean with Italian emigrants bound for America. He stayed with them and fully understood the difficulties that awaited them. He understood that schools, hospitals and points of reference were urgently needed. Cabrini soon showed that she had the spirit of adventure of an uncommon entrepreneur. She solved enormous problems, facing misunderstandings and prejudices (about herself, Italians, Catholics, etc.). It is all terribly complicated.

The young Cabrini wants schools, nurseries, hospitals and respect for her fellow countrymen. She managed to make herself understood, to involve powerful people, donors, cardinals, even Leo XIII the Pope who greatly appreciated her apostolate. She was a great entrepreneur for her brothers without resources, like the poor emigrants. She tracked down and helped her compatriots wherever they were, even those condemned to death with whom she was able to share a moment of light of rare Fraternitas.

Mother Cabrini’s sisters visited not only ghettos, but also mines, prisons, hospices, wherever there were poor Italians in poor conditions. They acted on the ground with more commitment than an embassy. They also managed to obtain the revision of trials with a favourable outcome for the condemned, penalised by their ignorance of the English language. Cabrini and her “sisters” indicated a particularly modern way of interpreting the Gospel. They collaborated in showing the way of the new times.

We seem to see in modernity, an indication on which she, with her activity, invited to reflect: the Earth with its resources is a good for all creatures, creatures cannot become a curse. Jesus Christ is Truth, but also Life. The time for each life is short, it is enough to reflect on this to understand that the time for peace is always urgent.

All of us – with a few exceptions – at this precise moment, we are sparing no time to dedicate to the current “migrant phenomenon”. Cabrini gives us a wake-up call to at least reflect and reason, to go deeper.

The ancient question: “Who are we? What do we want?”. As things stand in Europe, we must all ask ourselves the obvious question about the present and the future. If we were to ask Cabrini what he would do today with the phenomenon of migration, we would get a wise but, I fear, too bold answer.

~~~~

Two exhibitions by the artist Meo Carbone on the Saint of emigrants, in Codogno (November 13 – December 20, 2021) and Sant’Angelo Lodigiano (December 21, 2021 – January 16, 2022)

by Goffredo Palmerini

The tireless work of the artist Meo Carbone continues to tell the story of Italian emigration through painting and sculpture. This further and precious contribution of his is expressed with the exhibition “Madre Cabrini, l’Angelo dei migranti” (Mother Cabrini, the Angel of the migrants), dedicated to Mother Francesca Saverio Cabrini, which will open in Codogno at the Cabrini Museum on November 13 until December 20, 2021, then in Sant’Angelo Lodigiano, where the religious woman was born on July 15, 1850, from December 21 until January 16, 2022. It will be an important step in the significant path that the Artist has been pursuing for over 30 years on the theme of migration and, with this exhibition, the deepening of the extraordinary work of St. Frances Cabrini, after the previous exhibitions dedicated to her in 2016 and 2017, set up in Rome, Genoa, Milan and Chicago. The events, organized by The Dream Foundation, have the patronage of the Migrantes Foundation and the Institute of the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, the congregation founded by Mother Cabrini.

The catalog produced by The Dream Foundation is very accurate. The catalog contains contributions, in Italian and English, from the art critic Claudio Crescentini, from Sister Barbara Staley, Superior General of the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, from Monsignor Giancarlo Perego, president of the Migrantes Foundation and archbishop of Ferrara, from Lina Lo Giudice Sergi, sociologist and social psychologist, from Fabio Capocaccia, president of the CISEI of Genoa, and finally the contribution of the author. The exhibition, as soon as the evolution of the pandemic will allow it, may be set up in the United States, starting with New York.

Art is an extraordinarily attractive medium to bring people closer to the theme of migration and Italian emigration in particular, the largest diaspora in the history of mankind, if we consider that in a century or so, between the 19th and 20th centuries, almost 30 million Italians left their country for the lands overseas. Meo Carbone’s project is therefore a very commendable artistic path, if we think that the process of removal of memory, present in a large part of the ruling class, confines the history of emigration to the margins of our national history. A neglected phenomenon, yet so important for the country if we consider the descendants of the various migratory waves that have generated 80 million oriundi in the world, therefore another Italy much larger than the one within our borders.

Today, the glorious part of this history is well known – but not even that well – the successes and the prestige that the Italians of the generations following the first emigration conquered in all fields during this true epic. Much less is known about the painful part. The army of workers who left Italy for the lands of emigration, in fact, had to face unimaginable and dramatic human vicissitudes, fighting every day against suspicion and prejudice, often suffering oppression of every kind, having to face tough competition with unknown social systems and equally precarious working conditions.