A Saint in Seattle: Mother Frances Xavier Cabrini

In the south aisle of the west nave of the Cathedral there is a statue of a pale-faced woman garbed somberly in a black habit and black veil, with a large black bow tied beneath her chin. She holds a book and a bunch of violets, and, stepping forward, she presents to the viewer a simple silver cross. Sometimes this figure is mistaken for St. Thérčse, the Little Flower; and sometimes for the Blessed Virgin. But it is actually an image of St. Frances Xavier Cabrini, the only Cathedral parishioner (so far!) to have been declared a Saint by the Roman Catholic Church.

Francesca Saviero Cabrini, born in 1850 in Italy, would seem by her baptismal name to have been destined for missionary work. To be a missionary was the dream of her youth. Like all children, she liked to make paper boats and set them sailing on the water; but she filled her boats with violets, representing, in her imagination, “a massive flotilla of warriors for God, heading for China.”

Geography was her favorite subject in school. Fellow students remembered “how she kept poring with fixed rapture over the pages of the atlas, imagining her travels to distant places.” This ambition to be a missionary never received any encouragement, not even from her family. On the contrary, it earned her nothing but ridicule. “You, so small and so ignorant,” people would say. “You dare to think of becoming a missionary?”

After the death of her parents, she began at the invitation of her parish priest to teach girls at the parish school. Her heart was still set on religious life, but, thanks to the interference of priests who had other plans for her, she was rejected by the communities to which she applied. Her years of suffering and waiting were rewarded at last in 1874, when her bishop, Monsignor Gelmini, at last set her mission plainly before her. “You want to become a missionary; the time is ripe. I do not know of an institute for missionary sisters; found one.”

Thus Frances Cabrini became a foundress under obedience, which suited her very well. “Obedience. Oh, precious word!” she once wrote. “Word of revelation, ray of clarifying light that diffuses upon us from the Father the manifestation of the divine will!” Her love of obedience in no way hindered her own energetic activity. She soon discovered within herself an extraordinary talent for leading others, for making wise decisions, and for getting immense quantities of work done in a short time. All this in spite of being “so little and so ignorant”!

Love of God motivated everything she did and filled her with tireless energy. “We should traverse the whole world to make Jesus Christ known and loved,” she told her daughters. “A God who loves us so much! Can we not love him with all our souls, no matter what the sacrifice?” Her love of God was infectious. Being with her, the sisters “felt a great change come over them with an increase of strength, alacrity, and capacity. Most of all, she communicated to them the great confidence she had in God.”

The Institute she had founded, the Missionary Sisters of the Sacred Heart, expanded rapidly, and she established a series of houses in Italy before Pope Leo XIII asked her to go to the United States to minister to the Italian immigrants there. At that time between 50,000 and 100,000 Italians were moving to the United States each year. Most were peasants, without money, without education, and with very little English. In the U.S. they were treated as a despised minority and suffered deeply from the loss of their culture, especially of their religion.

On March 31, 1889 Mother Cabrini reached New York City after the first of many trans-Atlantic voyages, and immediately began founding schools, orphanages and hospitals in the face of prodigious obstacles. She approached the task with her legendary energy. “With your grace, my sweet Jesus, I will follow you until the end of my days and forever,” she would pray. “Help me, Jesus, because I wish to do so with ardor and speed.” Foundations in Nicaragua, New Orleans, and Brazil followed rapidly, and she came to Seattle in 1903.

“Here we are, not far from the North Pole,” she said, quite seriously, on arriving in the Pacific Northwest. She loved the young city, which she described in glowing terms (her childhood enthusiasm for geography stood her in good stead):

This city is charmingly situated, and is growing so rapidly that it will become another New York… The town of Seattle spreads over twenty hills; and though it is fifty degrees north latitude, it enjoys an interminable spring because of the current that comes from Japan… The bishop is very good. His name is O’Dea, and he is happy to have us in his diocese because we bear the name of the Sacred Heart of Jesus.

Seattle had a large population of Italian immigrants, and she found that “some of them have not seen a church for over 20, 30, 40, and 50 years.” She immediately set about remedying the situation by founding Mount Carmel Mission on Beacon Hill, followed by a school which later developed into Our Lady of Mount Virgin school and parish. In 1918 the sisters moved to a location on Lake Washington which Mother Cabrini had seen in a dream (Sacred Heart Orphanage, now Villa Academy).

In establishing Columbus Hospital she ran into difficulties. She had with much trouble and many prayers acquired the Perry Hotel which stood on Madison Street between Boren and Terry Avenues. Bishop O’Dea came to bless the building and asked her what she intended to do with it. When she told him that she wished to found a hospital, immediate objections arose. There were fears that this hospital would be too much competition for Providence, the only other Catholic hospital in the city, located nearby on Capitol Hill. Bishop O’Dea withdrew his support and in fact forbade her to found the hospital.

This opposition was devastating to her. “It is I who have alienated the blessing of God,” she told her daughters. “When I shall have gone, everything will be better.”

In her suffering, she had recourse to prayer, and she must have come very often at this time to pray at St. James Cathedral, just a block away.

When she left Seattle in November 1916, Mother Cabrini was already very ill. But before she died on December 22, 1917, Bishop O’Dea had relented, and she had the happiness of knowing that Columbus Hospital was well on its way to completion. Bishop O’Dea was the first bishop to proclaim her publicly as one of the greatest women of the twentieth century.

She was 67 old at the time of her death. She had long before chosen as her motto the words Omnia possum in eo qui me confortat-“I can do all things in him who comforts me.” The abundance of Mother Cabrini’s accomplishments seem to prove St. Paul’s bold statement true.

Quotations are taken from Mother Frances Xavier Cabrini by Mother Saverio de Maria, MSC, translated by Rose Basile Green. Mother Cabrini is commemorated in St. James Cathedral by a statue in the right hand niche of the west façade, a bronze relief plaque in the west vestibule, and by a statue in the south aisle of the west nave. Relics of Mother Cabrini were sealed beneath the altar at the time of the Cathedral’s rededication in 1994.

Maria Laughlin is the author of St. James the Greater, an illustrated history of the Cathedral’s patron.

Thanks to St. James Cathedral website

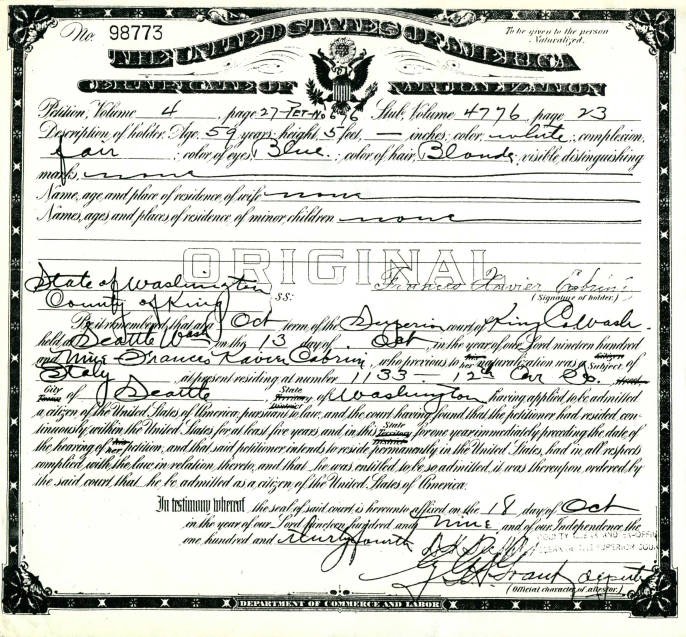

https://saintfrancescabrini.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p17305coll16/id/1/

We thank OCLC and Cabrini University for this certificate.

Me eduqué en el Volegio Sagrado Corazón de Jesús en la ciudad de Villa Mercedes en la Provincia de San Lui, Argentina. La Madre Cabrini era nuestra guía espiritual t todas sabíamos de los barquitos de papel con violetas que ella imaginaba llenos de misioneras qye llevaban el mensaje divino a lejanos países… Su obra fecunda y su vida de entrega al Sagrado Corazón de Jesus fue nuestro ejemplo de vida…